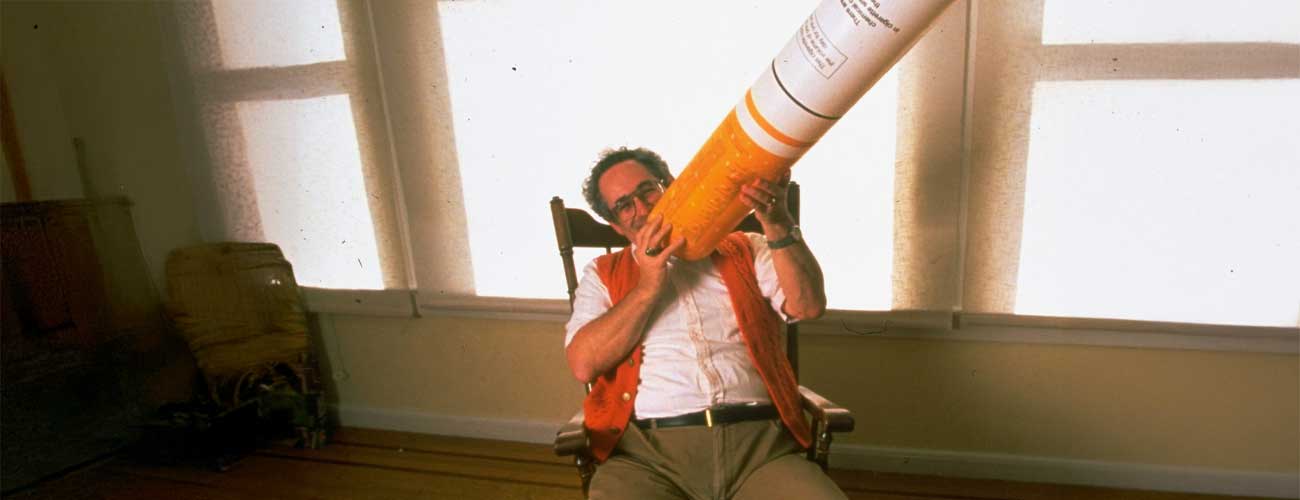

Stanton Glantz, a high-profile figure in tobacco control, has published a new blog post claiming that vapes “increase harm” and should not be considered a harm reduction tool.

The post, titled ‘E-cigarettes increase harm to smokers, so should not be promoted as a harm reduction strategy (in 10 slides)’, argues that vaping is no better, and potentially worse, than smoking.

However, there is no scientific evidence to substantiate this claim. The studies cited in the blog do not demonstrate that vaping increases harm for people who smoke, and no major evidence review has concluded that vapes are as harmful as, or more harmful than, cigarettes.

Here, we examine five of Glantz’s central assertions and assess how they align with the current evidence base.

1. Claim: Vape risks are “close to cigs”

Glantz states that “epi shows: ecig risks close to cigs,” citing 107 population studies and asserting “no detectable difference” in cardiovascular disease, stroke, metabolic dysfunction, asthma, COPD and oral disease between people who vape and people who smoke.

That is not a conclusion reached by major evidence reviews. Toxicology, biomarker and clinical data consistently show substantially lower exposure to many harmful and potentially harmful constituents when people switch completely from smoking to vaping. No large, authoritative review has found overall risk from vape use in adult smokers to be “close to cigs”.

2. Claim: Vapes were developed to “hold on to customers,” not for cessation

Glantz says it’s a “myth” that vapes were developed to help people quit, arguing instead that “e-cigs developed in 1990s by Philip Morris to hold on to customers,” citing internal documents.

But this skips over the fact that the first modern, commercially successful vape was created in 2003 by Hon Lik, a Chinese pharmacist, who designed it after losing his father to lung cancer. His stated aim was to offer a less harmful alternative to smoking – and that device drove consumer-led vaping as we know it.

Even if Philip Morris explored similar technology in the 1990s, what matters now is how current vapes are used. Modern devices are regulated, widely used for quitting, and largely shaped by independent innovation. Citing early industry prototypes says nothing about today’s evidence on harm reduction, and shouldn’t be used to dismiss it.

3. Claim: Dual use “always riskier”

Glantz writes “dual use [is] always riskier,” arguing that because “dual use [is] common,” accounting for it means “higher risk for average user,” including for respiratory and oral disease.

Dual use certainly blunts potential health gains, and public health guidance is clear that complete switching is preferable. But his assertion that dual use makes vapes a net negative for harm reduction is not supported by the evidence he cites.

Many people who eventually stop smoking altogether pass through a period of dual use. The relevant comparison is not dual use versus abstinence, but dual use versus continuing exclusive smoking.

4. Claim: Real-world data shows “no association with stopping cigarettes”

In discussing population studies, Glantz cites Wang et al. and concludes there is “no association with stopping cigarettes” in real-world use.

That framing omits the rest of the evidence base. The same slides acknowledge that randomised controlled trials under “clinical supervision” and “combined with counselling” find vapes “better than NRT,” even while adding the claim that “for every ‘switcher’ 1.9 to 3.7 dual users” appear and “so harm increased.”

The step from that trial data to a conclusion that overall harm is higher is not demonstrated by any study. It rests on assumptions about dual use rather than on measured health outcomes.

5. Claim: “There is no reason to accommodate e-cigs” in policy

Glantz’s “bottom line” slide states that “for many diseases vapes [are] as bad as smoking,” that they “keep people smoking and promote dual use” and that “e-cigarettes increase, not reduce, harm for adults.”

The conclusion is that “there is no reason to accommodate e-cigs or harm reduction in any laws or regulations or guidelines,” including Framework Convention on Tobacco Control guidelines.

No systematic review or guideline panel has concluded that vapes are “as bad as smoking” for adults who switch completely, or that they increase overall harm among people who smoke.

The policy recommendation in his blog isn’t based on scientific consensus, it reflects his own interpretation of selected studies.

Harm reduction needs facts, not just claims

Glantz’s core message is that he believes vapes don’t reduce harm and shouldn’t be part of harm reduction. But he hasn’t provided evidence showing that vaping actually increases harm for people who smoke.

Most research to date points the other way: for adults who smoke, switching completely from cigarettes to regulated vapes is likely to lower, not raise, their health risks.

That doesn’t mean vaping is risk-free, especially for young people, but it does mean harm reduction policy should be based on what the evidence shows now. Bold claims about “increased harm,” if not backed by solid science, risk misleading both smokers looking for safer options and the policymakers who regulate nicotine products.