That headline isn’t a rhetorical question: it was what we were genuinely thinking after we watched a YouTube replay of a conference call organised by the European Cancer League.

“How will Europe achieve it’s first tobacco free generation?”, questions the title of the webinar. Fair enough, we thought, so presumably they’ll talk about how to reduce the prevalence of smoking. After all, cigarettes are over 90% of the European nicotine market, and they kill half of their users. Right?

Wrong.

There was only a single mention of smoking during the whole hour and 40 minute conference call; and that almost served to underline just how far from the mission of reducing smoking related disease many in public health have come.

But why aren’t we talking about smoking?

Towards the end of the webinar, one attendee who asked an anonymous question received quite the response from moderator Mariam Zaidi, which we thought was quite telling. You can watch it in full below – we’ve started the clip where all this happened:

The question apparently asked was why the panel was only talking about e-cigarettes when traditional products still make up 95% of the market. Seems like a sensible observation. But Zaidi seemed shocked.

“I thought ‘there’s no way someone’s going to ask that question’”, Zaidi says by way of introduction, going on to scold the participant who had the temerity to ask it: “you really shouldn’t be asking this”.

Zaidi then goes on to suggest that the question was along the lines of “why should we even care about novel and emerging products?”.

Zaidi’s reaction to what should be a fairly basic question: why aren’t we talking about the products which dominate the market and kill people in a seminar on tobacco policy, speaks volumes about the contempt with which many in the public health establishment view those who offer even the slightest disagreement with their dogma.

But that’s not all…

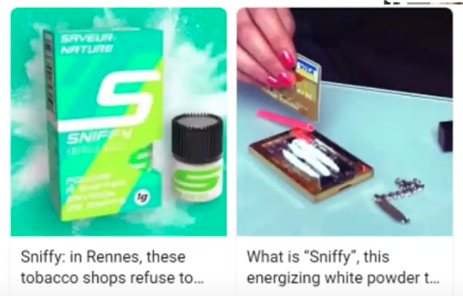

The oddness of the whole event started right from the beginning, when Lilia Olefir – who runs Europe’s tobacco control lobby “Smoke Free Partnership” showed the audience a picture of a French product called “sniffy”, which apparently can be bought in tobacco stores in France and which you seem to use like cocaine. Seems scary, huh?

But that’s exactly the point. We’d never heard of this product, and Google wasn’t helping, but luckily one participant, Dr Jerome Foucard, was on hand to explain.

“There is no nicotine in this product”, he told the audience in a matter-of-fact kind of way. OK – so why was it relevant to the Smoke-Free Partnership or to the webinar at all?

We can only assume that it was used to scare participants and regulators alike, never mind that it’s completely irrelevant to the debate: “it looks like hard drug use, so we’ll see if we can connect it somehow”, they must have thought.

Credit to Foucard – he mentioned a few times that vaping is clearly far less harmful than smoking, much to the annoyance of the representative of the WHO on the panel

Evidence free statements abound

We were also somewhat taken aback by the ignorance of some of the panellists about the products that they all hate so much.

“Data and evidence shows that those smokers that are 40-50 years old…they use tobacco flavour, they don’t use cloud flavour or candy flavour” asserted Carlos Torrado Ortega, from the European Cancer League. What data and evidence, we asked ourselves?

We’re happy to be corrected on this point, but we couldn’t find a single study that supports the statement that older smokers who use vaping to quit only use tobacco flavour, but we can find plenty of evidence to the contrary.

A lot of the analysis we’ve found is inconclusive, but those who have reached firm conclusions note the importance of non tobacco flavours for adult smokers who want to quit. One study from New Zealand concludes:

Flavours play a major role in vaping initiation for current smokers, former smokers and vaping-susceptible non-smokers, and remain important to those who continue vaping. Our findings highlight the need for regulation that allows some flavour diversity

Another, from the UK, hails the importance of advice on flavours specifically to aid quitting:

“The simplicity of tailored support through flavour advice and supportive messages could have a huge impact in helping people lead smoke-free lives”, the study’s author concludes.

True, these are two studies among many, and others question the role of flavours when it comes to cessation. But not one single study that we could find suggests that older smokers only want tobacco flavours. So why say it?

Ortega also showed more gaps in his knowledge when it came to nicotine pouches:

“You see all these colourful candies and you put them in your mouth, but what you don’t know is that they can have up to 40mg of nicotine in them”, he asserts casually.

Let us tell you, if you’re using a nicotine pouch with 40mg of nicotine, the unpleasant stinging sensation will let you know about it fairly quickly.

Ortega then goes on to tell the audience that “when you want more nicotine pouches, you will want more electronic cigarettes, and then you will also want to try normal cigarettes”.

Again, where is the evidence for any of this? We don’t know of any; what we do know is that an analog product – snus – has been on the Swedish market for decades, and cigarette use there has fallen to almost 5%: if Ortega were right, you’d expect Sweden to have higher smoking rates than anywhere else.

Fighting dirty

We could go on, but this gives you a pretty good flavour of what happened. The whole webinar is available on the European Cancer League’s YouTube channel for those of you who are masochistic enough to want to watch the whole thing.

But the point is this: the organisations who presented in this webinar – the WHO, the Smoke Free Partnership, the European Cancer League and so on – are desperate to get the EU to regulate safer nicotine products out of existence, their lobbying power is great, and they do not tolerate dissent. The next few years, when the European Union will decide whether and how to increase regulation on safer nicotine products, will be characterised by this kind of campaigning; consumers need to be ready to fight their corner too.